For decades, the hallmark of the American economy has been mobility—the freedom and willingness of people to pack up, move across the country, and pursue better opportunities. Whether chasing jobs, education, or the chance to own a home, Americans historically moved more than citizens in nearly any other developed nation. But today, that defining trait is eroding.

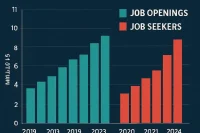

Recent data shows that U.S. residential and job mobility have fallen to historic lows. Only 7.8% of Americans moved in 2023, one of the lowest figures on record. Job switching, once a major driver of wage growth and professional advancement, has also plummeted. The United States is becoming a country of workers and homeowners stuck in place—locked down by high costs, shrinking opportunities, and a lingering sense of economic uncertainty.

This slowdown has far-reaching consequences. It threatens career growth for young workers, stifles housing supply for families, reduces overall productivity, and chips away at the dynamism that has long fueled the American Dream.

Table of Contents

Mobility at Historic Lows

Residential Stagnation

Mobility has been on a downward trajectory for decades, but the past few years have accelerated the decline. Homeowners who once upgraded to larger homes or relocated for new jobs are increasingly staying put. Rising mortgage rates have created a “lock-in” effect: millions of Americans refinanced at ultra-low interest rates during the pandemic, and moving today would mean taking on a new mortgage with much higher payments.

Renters are not moving either. The cost of relocation is prohibitive, with even short-distance moves costing hundreds of dollars and cross-country moves running into thousands. Coupled with record-high rents in many urban centers, renters often find that staying put is the only financially viable option.

Job Switching Slows

The labor market tells a similar story. Job switching, which traditionally offered the biggest wage gains, has slowed sharply. Employers are cautious about expanding, and workers are hesitant to leave stable positions amid uncertainty. For younger workers, especially new graduates, the result is career stagnation: fewer entry-level opportunities, fewer promotions, and less bargaining power.

U.S. Residential and Job Mobility: Why Americans Are Staying Put

Housing Pressures

High housing costs are the single most significant factor behind the decline in residential mobility. Limited supply in major job-rich regions like the coasts and high-growth Sun Belt cities has pushed prices out of reach for many families. Zoning restrictions, long permitting processes, and rising construction costs exacerbate the shortage, making it nearly impossible for new supply to catch up with demand.

For homeowners, the mortgage lock-in effect is particularly powerful. A family with a three percent fixed-rate mortgage has little incentive to move and take on a six or seven percent rate, even if it means passing on better job or lifestyle opportunities elsewhere.

Employment Trends

On the job front, employers are relocating fewer workers than in the past. The decline of corporate relocation packages—once a staple for upwardly mobile professionals—has made moving less appealing. Additionally, the rise of remote work initially boosted geographic freedom, but as many companies pull workers back to offices, the flexibility that once fueled pandemic-era moves has diminished.

Find Jobs That Fit Your Lifestyle

Search WhatJobs for remote, hybrid, and local opportunities—so you can build your career without unnecessary relocation.

Search Jobs Now →Demographic and Social Changes

An aging population also plays a role. Older Americans are far less likely to move, and as the median age of the U.S. population increases, overall mobility rates naturally decline. Dual-income households create another anchor, as coordinating two careers across geographies becomes more complex. Families are also less willing to uproot children from schools or extended family networks, reinforcing the tendency to stay put.

Consequences of Reduced Mobility

Career Stagnation

For individuals, reduced job mobility translates into slower wage growth and fewer career advancements. Workers who change jobs typically enjoy larger pay raises than those who remain in the same role. When employees feel locked into their jobs, they sacrifice potential income and skill development, which can have a compounding effect over a lifetime.

Housing Market Distortions

The housing market suffers as well. With fewer people moving, the cycle of upgrading, downsizing, or buying first homes slows. This limits available inventory, drives up prices further, and makes it harder for younger families to enter the market. The result is a feedback loop: low mobility feeds into tighter supply, which in turn discourages more people from moving.

Economic Dynamism at Risk

Economists warn that declining mobility undermines one of America’s greatest competitive strengths—its flexible labor market. Historically, workers moved to where jobs were, helping industries grow and regions thrive. When people stay put, the economy loses efficiency. Productivity suffers as workers and businesses fail to match optimally, and innovation can slow without the cross-pollination of ideas and talent that mobility fosters.

Keep America’s Workforce Moving

Post your job on WhatJobs and connect with top talent nationwide—helping businesses grow, industries thrive, and innovation stay strong.

Post a Job Now →Social Fragmentation

Beyond economics, the decline in mobility has social consequences. Americans are becoming more rooted in specific communities, which can reinforce cultural and political divides. Reduced movement across regions means fewer opportunities for people to engage with diverse perspectives and experiences. The country risks becoming more geographically and socially siloed.

Spotlight: Young Workers in Limbo

Perhaps the most troubling consequence is the effect on young workers. College graduates traditionally fueled mobility, willing to relocate for their first job or follow opportunities across state lines. Today, student debt, high housing costs, and scarce relocation support keep many graduates tied to their hometowns.

A young engineer in Texas, for example, might apply to hundreds of jobs nationwide, but without relocation assistance, the practical cost of moving can make even the best offer unattainable. Instead, many remain underemployed locally, delaying career development and lowering their long-term earnings potential.

What Can Be Done?

Experts suggest a range of solutions to reverse the mobility decline:

- Housing Reform: Loosening zoning laws and streamlining construction permits could increase housing supply and reduce affordability barriers.

- Relocation Incentives: Public policies like moving vouchers, tax credits, or relocation subsidies could help families and workers access opportunities outside their immediate regions.

- Remote Work Expansion: While companies are pulling back, investing in remote-first roles can reinvigorate geographic flexibility without requiring physical moves.

- Education and Training: Better pathways for career transitions can make job switching less daunting and more accessible.

Ultimately, restoring mobility will require coordinated action from both government and private employers to ensure that Americans are not trapped by geography or financial circumstance.

FAQs: Understanding America’s Mobility Crisis

Q1: Why are fewer Americans moving today compared to the past?

A combination of high housing costs, mortgage lock-in effects, fewer relocation opportunities, and an aging population has steadily reduced mobility. Families and workers face both financial and social barriers to moving, making it less attractive or feasible than in previous decades.

Q2: How does low job mobility affect wages?

Workers who switch jobs typically see higher salary increases than those who stay in place. With fewer people moving between jobs, overall wage growth slows. Younger workers, in particular, lose the chance to build skills and negotiate stronger pay early in their careers.

Q3: Does low mobility impact the housing market?

Yes. When fewer people move, housing inventory tightens. This keeps prices high, restricts options for first-time buyers, and discourages downsizing or upgrading. The cycle feeds back into itself, reinforcing the freeze in both housing and job mobility.

Q4: What can policymakers do to improve mobility?

Policy tools include expanding affordable housing, offering relocation assistance, reforming zoning restrictions, and encouraging remote work opportunities. These measures can help restore flexibility for both workers and families seeking better opportunities.

Conclusion

Mobility—once a cornerstone of the American Dream—is faltering. With fewer people moving homes or switching jobs, the United States risks a generation of workers and families stuck in place, unable to chase opportunities that previous generations took for granted.

The decline in residential and job mobility is more than just a statistic. It reflects a fundamental shift in how Americans live, work, and build their futures. Unless addressed, it could leave the nation less dynamic, less innovative, and less equitable.

Reversing the trend will not be easy, but the stakes are clear: without mobility, America risks losing one of the engines that has long powered its economic and social progress.